On July 20th, 2014, I fell off a ledge on the side of the West Lion. My backpack shifted, the rock was slippery, and I went down fast. I slid a meter or two, feet first, hugging the wet rock. My chin took a glancing blow from the place my feet had been moments before, and I landed on all fours on a steeply pitched slope. The weight of my multiday pack flattened me out, and I slid another 15 meters downward, unable to compensate or slow my speed. My world filled with sound, the grinding roar of my backpack’s metal frame on rock, my brother yelling and yelling above me. After a few seconds I ran out of ramp, dropping into a cluttered gully of broken rock. My feet locked in, and I stopped.

“Calm down,” I called to my brother. “I’m all right”. But I didn’t feel all right. I was ten kilometers from the trailhead, on one of BC’s most technical through trails. We were surrounded by cloud, insulated against most forms of rescue. My left knee was starting to throb, as a 3 inch gash got ready to bleed. This was all pretty bad, but what hit me most was a horrified sense of responsibility. I was here with my son, my three year old hiking buddy. He was with me now, crying in the backpack, shaken but unharmed. I had fallen with my son.

It wasn’t supposed to be like this. When my brother Kyle changed our plans to include the Howe Sound Crest Trail, he swore up and down that it was family friendly, a literal walk in the park. He had already done the north and south sections, leaving only an undefined middle part. I interviewed him extensively on the topic, then researched the trails myself. The BC parks brochure admonished me to watch my footing and stay on the marked path, things that I was very good at already. Internet forums were full of chest-thumping tales, where sweaty masochists discussed how fast they had “done the crest”. If it took these boisterous brutes 9 hours, couldn’t we do it in three days? My brother and I were strong, experienced hikers, with the tenacity and general disposition of mountain goats. There was nothing ahead of us that should pose a problem.

The first day played into our expectations, rising steeply but smoothly though beautiful stands of hemlock and cedar. Waterfalls fell around us while Ryan snored gently in the Deuter pack, a heavy but robust carrier not unlike a fabric Humvee. Secured in his five point harness and wrap-around cockpit, Ryan would be my constant companion for the next three days, alternately singing, laughing, sleeping, burping, and asking where the parking lot was. We were multiday hiking, one of the best things on earth. The forest was our home, and we were awesome.

The second day was even easier, a short haul between friendly campsites along the trail. Thick cloud had set in, as forecast. Our views faded away, but there was beauty all around. Heather and wild blueberries, yellow lichen shining in the diffuse light. The path was simple, weather-worn with the boots of all that had come before us. We spent a quiet night at Magnesia Meadows, with glimpses of the distant city through pockets in the cloud. 14 clicks remained of our 29k hike, and Kyle knew that the last 8 were easy. There really wasn’t a lot to do, but I was worried. Something I had read about crossing the Lions, some inner sense that I would be leaving the edge of my comfort zone. As the sun went down, I texted my wife goodnight. “Tomorrow we pass right between the Lions!” I told her with exclamation points. After some hesitation, I decided not to say that I was afraid.

We hit the trail at 6 am, drifting past the other tents like Gortex wraiths in the rising fog. Ryan had woken us before the alarm, speaking out of the inky black. “I know it’s just a dream,” he said, “but I think the Little Daddy is out there. If you look out the window you might be able to see him, walking in the dark.” That was suitably ominous, although not as bad as something he said three weeks before, as we sat in the living room. “Daddy, are you falling?” he asked abruptly. “If you’re falling, you have to duck your head.”

The trail took a beating just past the campsite, almost lost under steep fields of wild blueberry. Our pace slowed as we skidded and slid along, soaking ourselves to the bone with bits of cloud and bracken. In the midst of this purgatory, my most peaceful memory of the trip: an impossibly small pygmy owl, gazing bashfully at us from the branches of a fir tree. Turning his head 360° to look at Kyle, then all the way back to me, showing off in the sudden perfect stillness. A moment without cameras, without almost anything. And then onward.

This part of the Howe Sound Crest was something new, something not entirely expected. Each stage took a bit longer than planned, each scree field a little crazier. These slopes were active, shifting slightly around us. Out there in the fog we could hear movement like muted thunder. We soldiered on, each step bringing us further into the crazy zone. In one of these fields we passed two middle aged men hiking like war refugees, shell-shocked and grim. Poor chaps, I thought. Bit off more than they could chew. Then a trio of trail runners, improbably energetic. 30 seconds after they left, I realized I had once run side by side with one of them, down the Sunshine Coast Trail. That moment seemed so far away, a different person’s memories. We passed over a ridge that dropped sheer into the clouds on either side, as I held a rope that had certainly seen better days. Maybe this was the place I was worried about, I thought. I stepped onto solid trail and began to feel the stirrings of hope.

We had been hiking 8 hours when I reached the first ledge. Just a rude cut in the wall of the mountain, embossed with defiant graffiti arrows. How could this be? We were caught flatfooted, totally unprepared for the sight. The good trail, the promised land, was still a few km ahead of us. The way behind was full of hazards enough, and so, I crossed the ledge. And it was fine. I passed along some more mountain track, reaching another ledge. That too went easily by. And then I reached the third ledge, what turned out to be the last one. The final place were you crab along, facing the rock, holding on to wet stone. No cracks and crevices, just the rough texture of granite to press yourself against. The drop was small, but I didn’t like the run-out below. It looked bad, disappearing off into the mist. Kyle got along just fine, and then it was my turn. I put my fear aside, crabbed along the ledge, got to a place I didn’t like. I could feel my centre of gravity pulling back, tugging at me with eager hands. So I fled back to safety.

“I’m worried about this,” I said to Kyle. “It seems like I’m at my load capacity.” I really was, although I didn’t know how close. I had been pushing margins all morning, and the boundary was about to give. I tried the ledge again, this time taking one more step. The crack I was standing in was not flat anymore, canting slightly downward. I felt my centre of gravity change, and I braced against it, calling for help. Kyle started taking his pack off, a process he wouldn’t finish until I hit the scree field some 20 meters away. I remember looking at my two hands, arched over this little hump of rock, each finger pushing in. For the first time on the hike, first time in years, I wasn’t sure if I had a good grip. And then I was falling, and all the fear was gone, washed out of my mind. I was falling and I hit the rock and I was still falling.

“Well, here I am,” I thought. “Sliding down a mountain. And I’m still fairly intact, which means I survived the first bit. Now I just have to wait.” And I slid along with the backpack frame roaring and the world blurring before my eyes.

There had been other ways to get past the ledge. None of them were great, but there were choices. I could have backed off further, divided up the backpack, enlisted Kyle’s help in a reasoned and proactive manner. I could have picked my way along the slope I was now racing down on my tummy. We could have tried to do something with our rope. There were a lot of choices that I didn’t take, because at 8 hours in you tend to go with whatever looks best at first glance. It’s actively dangerous to stand around searching for perfect ways to do things, because energy (and daylight) are so finite. I thought I could make it in safety, so I took the chance. Usually things work out, and in fact they still worked out. I skidded to a halt, and Kyle ran up to me, shouting apologies into the rain. He got the backpack up, confirmed that Ryan was intact. My son was crying freely, so Kyle held his hand. Ryan says it was this moment when he started to feel happy again, out there on the bitter edge of the north shore mountains. As for me, I crouched with my legs hugged to my chest, staring out into the fog. The aftermath was hitting, and I had to be strong. I hid the tremors from my son, let them go into the wind. I didn’t know then if I was capable of walking, let alone carrying him another 10 kilometers out. And I felt so bad about it, like I had stepped into the path of a car while holding his hand. Like I had really messed up, despite trying so hard. Messed up not because I fell, but because I had allowed myself to reach a place where falling was so easy. I came with nothing to prove, I didn’t visit these parts to learn how hardcore a dad I am. I just want to show him the world.

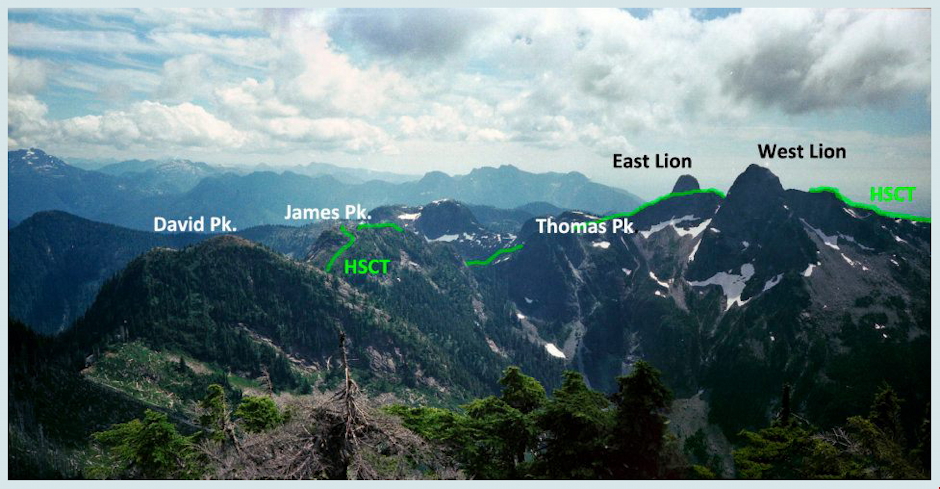

- This is what the world looks like, when you can see more than 10 meters. Our route so far that day. Image © Hollyburn Heritage Society.

There was no time for regret. My mind was already stepping towards what was next, a sprawling list of question marks. I sent Kyle back up the hill to grab the first aid kit, then spoke to my son in a strong voice, a voice from a deeper part of me. “Ryan, we fell down, and I bumped my knee. But I’m going to fix this, okay? Daddy is going to fix this. I promise.” I’m going to fix this injury, this mistake, this place we’re in. I’m going to get us out of here, although I don’t know how any more. I’m going to do it, absolutely. “Yes,” my son said, and he stopped crying.

I pulled out my phone to check for service, and found that it had been bent into an arc by some unseen blow. I stood up on the scree slope, blood trickling down my leg, holding the world’s first curved iPhone. Feeling kind of ridiculous, I bent it back into shape. Everything was still working, and I texted Katie. “I can has injury”, I wrote sadly. It was 1:30 PM, with the day halfway done. The highest part of the hike was still ahead of us.

“What do you need?” her reply came back. No alarm, no demands for answers. Just support, immediate and real. The way it always has been.

“I don’t know,” I replied. Tiny raindrops fell on the Ziploc bag I held over my screen. I needed to get my son home, but I wasn’t sure how any more. I needed help, but help seemed remote, far away. I dreaded making the call to Search and Rescue, telling them that Dad of The Year Joseph McLean was stranded in impossible terrain well beyond the pickup points, so come and get me, boys! Hope you like carrying a stretcher up sheer mountain passes. And by the way, I totally brought a three year old! I tied a clumsy bandage around my leg, daubed at my chin with a moist towelette from the kit. In a few minutes I’d try to climb out of this gully, see if I could still be some use. Otherwise I would have to make the call. My first aid towelette had dried out long ago, giving it the shape and texture of a saltine cracker. Typical, I thought. Typical. And that’s when I heard the voices of our rescue team.

The Howe Sound Crest Trail is a lonely place, especially when it’s being harassed by rainclouds. Although we had met a few parties heading north that day, no one else was going south towards Cypress. No one except Peter, Colin, and Natalie, who strolled out of the fog just ten minutes after my fall. They navigated the ledge with something approaching ease, walked down to us on the slope. Was I okay? Maybe. Was there anything they could do? Well… could someone help carry the kid? Just for a moment, just up to the next crest. My legs seemed to be working, but I was still unsteady on my feet. I didn’t want any more surprises for poor Ryan, not even a stagger. And that is how he came to meet Peter, or more precisely, Peter’s back. Up into the air went my pack and my boy, and off they went for the top. I called after Ryan that Peter was a good hiker and very strong, silently praying that my snap analysis was correct (some people can’t even lift the carrier). At any rate, the man was an alpine ox. I scrambled ahead, feeling buoyant without a pack. Marvelling that my knee still worked, with a gash the size of a slug. Soon we were at the top of some anonymous peak, looking back at vague ripples in the clouds that could have been mountains.

And still I hesitated, unsure if I should ask for more. I had a full range of motion in my leg, and a fine show of strength from the adrenaline coursing through my veins. If Kyle cleaned out most of my pack, I could still carry my boy. But the trail ahead was rough, with promises of more “technicalities” before the last easy grade home. I just wasn’t sure, and I said so. “We’ll stay with you for a while,” our nonchalant saviours said. “Until you get sick of us.”

And that was that. Well, that plus other things, too many to tack on. Seven more hours of hiking, no one getting sick of each other. Restorative garlic sausage on one of the countless summits of Mt. Unnecessary. Washing out my wound, which also looked like sausage. Laughing with real warmth, even as the day around us grew cold. Playing musical backpacks, so that I was left with the lightest one and Ryan was paired with his new best bud. Watching my son going up crags in his undamaged backpack, passed from hand to hand by three strangers who were fast becoming friends. Meeting my sister-in-law near km 27, just half an hour from our car, as twilight settled in to the woods.

- Kyle was not letting go of me again. With Peter and Ryan on Mt. Unnecessary. Photo by Colin Alexander

I took Ryan onto my shoulders for the last steps down. We were both coming out of our daze, waking up to the fact that everything was already okay. Ryan spoke up for the first time in ages, reminding us that the sound we just heard, the distant fading sound as we walked the final steps to the parking lot, was the hooting of the last woodland grouse. The soft farewell of the forest, and a smile from my child. I was utterly amazed that we were out. The feeling would last through the next sunrise, when I got back from the hospital to see Ryan sleeping peacefully on cotton sheets, as if he had been there all along.

On July 20th, I fell off a ledge on the side of the Lions. I gained some bruises, a few scratches, 8 prim stitches just below my knee. And something changed. Something left me that day, a barrier I had raised between myself and the world. I learned what it is to ask for help from perfect strangers, and I leaned that I have a unshakable strength for getting home. I found out what it’s like to betray a sacred trust and win it back. In the days following, I felt deeply ashamed, damned by my own foolishness. I was afraid to tell people where I had taken my son, afraid to admit that I had been so stupid. Slowly, as my leg healed, I came to accept what happened to us as almost normal, and to take solace in our response. I’m not proud of the event, but I’m proud of what was left. We got out together, and we were smiling. I didn’t break my bones, I didn’t hurt my son. And I didn’t break our love of the great outdoors.

Falling is the original teacher, and this fall changed me. These days I feel more powerful and more vulnerable than before, although in a way I’ve always known this. Truly, we are so good at hiding things from ourselves. Our purpose and our power, our strengths and our failings. Out there on the mountain, I met up with ground truth (and hard). It hurt, but I heard. I left some blood on the rock, and some pretense also. This shell may grow back, but for now I’m closer to myself than I was before. I’m closer to ground truth.

—

Ryan talks about our fall every day. His verdict is that Daddy took a step that was too big, and then Peter came to help. My stitches are finally out, and we just went on our first hike together again, on the good old Sunshine Coast Trail. He was bugging me for so long, when would my knee be ready, when could we go for a big hike, and would I fall down again. As it happened, I did slip on some moss, and he scolded me very sternly to be careful. Then he nodded off to sleep, trusting me to do my best. His soft breath sounded in my ear, and I walked forward, leg still a bit stiff but working well. Forward with careful, humble courage. On towards whatever lies ahead.

wow, exciting scary story, Joseph, and excellent writing.

Beautiful. Also is our wild dangerous back yard and how you play in it with your son.

Wonderful writing. Thank God that no was badly hurt in any way, that it will be part of your “story”, and that you both were able to “get back on the horse”.

Incredible. Another example of how the outdoors can shape both our character and our life path. Truly reminded me of reading a piece by John Krakauer or Sebastian Junger. Would you consider submitting this to Outside Mag?

Thanks TMc. Those are some heavy names you’re dropping. Sure, I would contribute to Outside Mag. I’m route-finding my way into publishing.

Congratz Joe! on so many levels <3

great story, Joseph; you create such clear images; I feel like I’ve been up there too: )